I’m struck by how common it is these days to hear people working in government say some version of ‘bureaucracy is broken’, ranging from senior civil servants to political appointees.

These are thoughtful people, so their point isn’t that everything in government is broken. They’re just saying that the problem runs deep — that it’s not enough to try harder, or to run things better, because at least part of the problem relates to the logic by which bureaucracy functions.

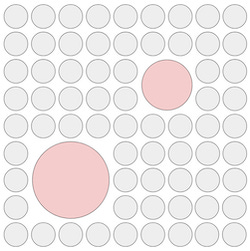

If that’s right, what do we do about it? A principle I find helpful is the idea from systems theory that when a system fails we need to work at the level of the problem.

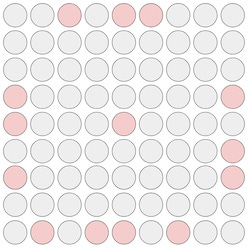

The point is that we rarely go deep enough. We use almost all of our collective capacity trying to run the system better, or at best trying to ‘reform’ the system, by which we tend to mean moving its parts around via changes to the ‘machinery of government’. Meanwhile the deeper mentalities, dynamics, and incentives that determine how the system functions go on largely as before.

One way to think about this is to imagine driving a car which is going slower than we’d like. If the car is working fine, then we can just push the accelerator. But if the engine is broken, then we’ll need to get under the bonnet — we’ll need to do some work ‘on’ the system, as opposed to working ‘in’ it. And if it turns out the car is going slowly because the road is flooded with six feet of water, and we’re floating, then we’ll need to change deeper aspects of the car’s design and engineering to fit the new environment.

This is all very abstract, which is one of the problems with talking about systems. So in this post I thought I’d name some practical examples of what it looks like to work on the system, as opposed to in it.

As ever, I’m thinking in the open and I’d be interested in feedback. This links to some work I’m exploring with Sophia Parker at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, which will go broader than I have done here to look at the craft of systems transitions and how leaders in struggling old systems can support the emergence of alternatives.

For now, though, here are seven practical things we can do to make big bureaucratic institutions less sclerotic.

Seven ways to save bureaucracy from itself

1. Create legitimating environments for reformers

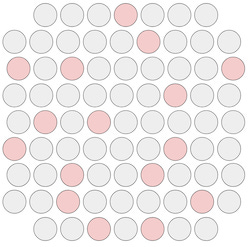

There are already thousands of people trying to modernise our governing institutions from within, but they get squashed by the system around them. We can therefore help the system adapt by carving out space for reformers. We can do this with small amounts of funding to legitimise people’s efforts, or by endorsing people’s work with prizes, or by leaders celebrating the work. We can invest in the places reformers meet, which helps to keep people motivated during the thankless task of reforming a system against its wishes and also helps the work of change cohere into a movement (e.g. see OneTeamGov or TransformGov). We can create escalation routes to help people bypass old-fashioned managers. And we can harness the insights of reformers in more systematic ways to drive change up through the system, e.g. see the bottom-up model of public service reform being developed by the Cabinet Office, or techniques like collective intelligence.

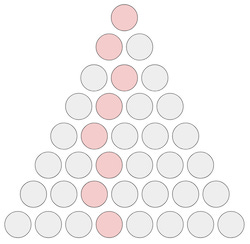

2. Help change spread via professions

History tells us that public institutions often adapt when a new profession emerges and spreads, so another good way to help a system adapt is to support new methods and disciplines. The profession acts like a vector, wicking new approaches across the system. See, for example, the rise of statistics in the 18th and 19th centuries; the spread of scientific management via the discipline of engineering in the early 20th century; and the rise of economics from the 1950s. Or more recently the spread of behavioural economics and the ongoing spread of design.

In a recent post I named a host of more nascent disciplines — from participatory governance to techniques for fostering community agency to deliberative methods — that are at an earlier stage of this process. We could help public institutions adapt by backing these new disciplines, for example by creating Centres of Excellence; and by codifying them into professions, as we did with digital roles; and by supporting new disciplines with Research Council funding. If we wanted to be bolder, we could make Britain a centre of energy for new techniques by creating a National School of Contemporary Governance.

3. Modernise some important outmoded processes

One reason bureaucracies get stuck is that old-fashioned proccesses at the top of the system inhibit change across the whole system, keeping people locked into outmoded ways of doing things. This is part of a more general issue that the top of a system is often the most old-fashioned part, yet it has the most power, which is one reason hierarchies are brittle.

The two blockers that come up most often when I talk with people trying to modernise government are processes relating to (a) budgets/business cases and (b) accountability.

The processes that emanate from the Treasury related to budgets/business cases lock people across government into an industrial-era model — a world of linear planning, upfront specifications, and building work around projects and point solutions. This is the opposite of contemporary management, which is about creating an environment in which a team can iterate their way towards an outcome. The business case process also inhibits innovation because it insists on narrow evidential criteria. In essence, the bureaucracy says it will only fund work in its own sclerotic image. This is a good example of a control mechanism backfiring, because it stops the system from discovering and spreading new ways of doing things.

Political accountability now also often inhibits learning and adaptability. In theory, of course, democracy is supposed to make government more responsive, which still works on some level, but the way accountability functions in today’s media environment now often creates inertia.

The problem is partly that politicians feel an intense urgency to deliver, which causes endless wheel-spinning — senior people push for quick solutions, which drives frantic activity but no forward movement. This problem is worst on the most complex issues, where government has the least traction. It’s not uncommon, on issues like multi-generational worklessness, that we’ve been spinning our wheels for decades. A politician enters office, hits the accelerator, spins their wheels, gets nowhere, and hands to the next person, who does the same.

As well as urgency, politicians feel a particular pressure to announce solutions. This again encourages old-fashioned leadership in which answers come the top, far away from the problem, and are sent to the edges to deliver. The alternative is to empower people to work close to the problem, innovating and testing ideas in quick feedback loops. In reality, this delivers more over the medium-term because it means the system learns, and progress accretes, but this is hard to explain to senior people who feel pressure to come up with an answer themselves.

The point, again, is that we don’t have do things this way. There are lots of agile ways to finance work: we can fund enduring outcome-based teams, and we can fund portfolios of small-scale experiments and scale the ones that are promising. We can also learn from forward-thinking foundations who fund in more patient ways, recognizing the importance of enabling infrastructure — digital, data, civic, etc — and who accept a richer range of evidence. As to accountability, we can use a whole suite of outcome-based approaches. Indeed we could do worse than learn from our experience during the Covid-19 pandemic, when regular outcome-based press conferences drove a focus on outcomes across government.

Changing these critical drivers of behaviour would help bureaucracy to adapt — learning from, and catching up, with its environment.

4. Kill old institutions and grow new ones

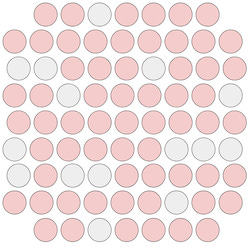

The public sector is brittle partly because it’s bad at killing old institutions and scaling new ones. There’s no equivalent to the cycle of creative destruction that happens in the private sector, which acts as a source of renewal and drives the diffusion of new practices.

Some people conclude that we need more competition in the public sector, but this only works under certain narrow conditions. The more general insight is that we need a more dynamic cycle of birth and death, and there are many ways to achieve this.

One way to do this is with regular pruning, like cutting back deadwood when gardening. We can periodically shut down old, underperforming institutions in what is sometimes called a bonfire of the quangos. This is not about cutting for the sake of it, but to clear space for rejuvenating new growth — closing down old institutions, and scaling promising new ones.

Having spent big chunks of my career helping to modernise old institutions, I know the pace of change is glacial when we try to modernise institutions in the absence of any system-level pressure to do so. These days I’ve come to think we should spend far more of our time working on the system-level processes of birth and death. We should have standing mechanisms to assist the death of old institutions, and to seed and scale new ones, and we should put a lot of effort into this process. We should hone the craft of starting a new version of an old institution, systematically transferring over the functions of the old institution, and then shutting down the old institution.

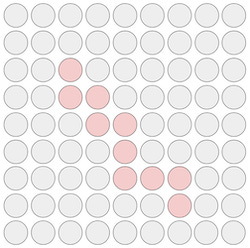

5. Fund work at the edges

I argued in a recent post that the edges of government/civil society are more contemporary than the centre, at least at the moment.[2] There are good reasons for this — the edges are closer to the environment, they have quicker feedback loops, they have no choice but to be pragmatic and adaptive, and they are less mired in the sticky sociology that makes the centre sclerotic.

I spend a lot of my time these days alternating between the centre and the edges and these differences are increasingly stark. If you visit the best community healthcare initiatives, for example, you’ll find them to be responsive, trusted, holistic, preventative, intentional, and agile in their institutional forms (e.g. they tend to be networks, not hierarchies). Meanwhile, in tired parts of Whitehall, teams work by rote to decades-old bureaucratic procedures, under outmoded leadership practices (work-hoarding, compliance and control mechanisms), housed in industrial forms (functional hierarchies, silos, teams named after deliverables).

This means we can help the system adapt by pushing money to the edges. However, this only works if we avoid central government’s nasty habit of funding work at the edges with the caveat ‘you have to work the way we do at the centre’. This goes back to the point above about funding criteria. We need to see work at the edges as a discovery mechanism, not just as capacity to deliver the centre’s wishes. We need to get over our addiction to funding pre-specified, time-limited projects and point solutions, and broaden/relax our evidential criteria and reporting requirements.

Again, there are lots of ways to do this, most of which are already used by leading foundations and forward-thinking parts of government. We can fund portfolios of work to spread risk, we can provide unrestricted and core funding, and we can be open to a broader range of evidence (e.g. techniques like Theory-Based Evaluation, which are less fussy about the way work is delivered). We can also use techniques like funding lotteries and challenge prizes. Some people will say this sounds risky, but again the point is to reduce risk at the level of the system by uncovering and spreading better ways of doing things.

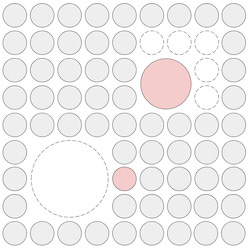

6. Loosen up / take small risks to stop big ones

When things start going badly in government, you’ll often hear people say politicians or officials should ‘get a grip’. This is understandable and it makes sense if the system is functioning well. However, if aspects of the system are broken, then gripping tightly can be counter-productive.

One general problem with ‘getting a grip’ is that we tense our muscles, making the system more rigid. For example, we get more fearful of the risk-taking required for innovation.

More specifically, ‘getting a grip’ fails during system breakdown because the rules/procedures you are gripping to are themselves broken. In this case, getting a grip is like tying yourself to the mast of a sinking ship.

A good example to learn from is the software crisis of c.1965–1980, when projects at big technology companies started to spiral into overruns. At first companies responded by imposing ever more intricate control mechanisms, which made the overruns worse. Firms later realised that these industrial-era control mechanisms were the problem — they didn’t work for the complexity of software development. The solution was to develop/adopt a new class of management practices, namely agile — small, self-sufficient teams working in quick iterative cycles.

The public sector is still learning the lessons from the software crisis. For example, we saw the exact same dynamic play out in the UK during the early failures of Universal Credit. DWP’s initial reaction was to use old-school control mechanisms, which made things worse, before the department pivoted to a test and learn approach, which saved the programme. (See The Radical How for more on this case study.) Many parts of government have still not learned these lessons.

To save our struggling bureaucracy, we need to get better at resisting the generic instinct to ‘get a grip’, which needless to say does not mean having no grip. It means we’ll often get more traction, and be more adaptable and resilient, if there’s some ‘give’ in the system. It’s similar to how engineers design buildings to sway in an earthquake, or make joints that flex.

The answer here partly goes back to agile and purpose-driven management practices— delegating decision-making to teams, and cultivating people’s capacity to learn and deliver well, close to the problem. Another key step is to work in the open, so that information flows freely, allowing you to adapt in increments in response to feedback rather than waiting for a crisis.

This whole issue of risk and adaptability is something the UK government is struggling with. For example, the government has recently tried to stop senior civil servants from speaking publicly, requiring them to get high-level clearance. This is an example of the system hurting itself — by inhibiting information flows, the system becomes more brittle. The instinct to enforce strict party discipline is another example, since it inhibits Parliament’s function as a way to test ideas — using mechanisms like EDMs, Westminster Hall debates, APPGs, Private Members Bills, etc — to open up debates and see how people react.

The key point is that mechanisms like these — working openly, allowing MPs to test ideas, etc — reduce risk at the level of the system, making the bureacracy and public institutions less brittle, and the government’s agenda less stale.

7. Use moral agency as a solvent to dissolve sticky habits

The last example is the hardest to implement but I also think it’s the most powerful. It’s about shifting the culture of a bureaucracy so that people turn off autopilot and make more intentional decisions.

In the book I’m writing about how we govern in ways that are more human and responsive, I’ve noticed that moral agency often plays a central role. This is a big part of the change story you’ll hear, for example, in pioneering Local Authorities like Camden and Wigan, which have adopted more human approaches and improved outcomes for residents.

This makes sense when you think about the nature of institutions.[4] Institutions like bureaucracies are sticky patterns of behaviour, in which we outsource decisions to a shared norm — rather than deciding fresh each time, we simply adhere to the norm. The extreme example of this backfiring is of course what happens in authoritarian regimes, when normal people do appalling things because they are ‘just following the rules’. The more mundane example is what happens every day in mature democracies like Britain, when bureaucrats crank the handle of processes they know are broken — see the Treasury civil servant insisting on the old-school business case, or the council worker firing off an automated debt collection letter to a resident who suffers from paralyzing anxiety, or the Job Centre adviser who is just ticking boxes.

To make the system less sclerotic, we need to uncover the human being in these situations, but without creating a free-for-all. Moral agency can do this by acting as a solvent, cutting through sticky behaviours. One CEO of a pioneering council I spoke to described this as a process of ‘waking up’. It’s as if staff snap out of a trance, suddenly seeing the human being in front of them.

This idea of spreading moral agency might sound like a dark art, but once again the craft of it is well-established. Camden ran master-classes, peer coaching, and CPD on relational methods. They also set up a Centre for Relational Practice that emphasises helping the human in front of you. Wigan used a ‘BeWigan’ culture-change programme, putting 7,000 staff through an immersive, values-based training experience. They also gave frontline staff permission to waive rules in citizens’ interests. More generally, we can draw on a suite of empowering management practices (e.g. see Dan Honig’s Mission-Driven Bureaucrats). None of this is to say that cultivating moral agency is easy, but it’s doable.

That was a canter through a lot of material. More could be written about all seven examples, and indeed I think unpacking these more — codifying these techniques, writing guides for how to do them, translating them into CPD, and so on, is very important.

This is why I’ll shortly be starting a range of work related to systems adaptation. This includes some work in the UK to map and codify the energy at the edges, and a series of conversations in Australia with public sector leaders. As I mentioned at the outset, I’m also exploring some broader work with JRF to support leaders in public institutions with the craft of system adaptation/how to usher in alternatives. Finally, I’m doing various advisory work to help public sector and civil society organisations use these techniques. For example, how do you fund this kind of work? How do you evaluate it? And so on. Watch this space for a new organisation to support this work, and in the meantime drop me a line if you’d like to work together.

For now, the nutshell version is: (a) it’s useful to think about our predicament as a form of system breakdown, because this reminds us to spend more time working on the system, not just in it; (b) we know how to do this work, even if it’s a bit unfamiliar and difficult; and (c.) we need to start expecting public sector leaders to have these skills, and we should do more to help people acquire and practice them.

I’m a writer and strategic consultant helping organisations adopt more human and contemporary ways of working. For more on similar themes, see this post on the energy at the edges of the system, or this one on more organic approaches to evidence. Drop me a line if you’d like to work together. You can follow my writing on Blue Sky, Medium, or Substack.

Footnotes

This issue of people being promoted for sustaining the system, not for changing the system, is starting to shift as more people recognise the urgency of the situation. It’s been interesting recently to see more people promoted into senior roles in government because they are known to be good at using these kinds of techniques. Still they are in a tiny minority in the senior civil service.

Note that by ‘edges’ here I don’t just mean ‘local’, as opposed to ‘central’. An old-fashioned council is just as sclerotic as any team in Whitehall, and indeed old-fashioned councils are one of the main blockers to innovative community-level work. By ‘edge’ I mean something more like ‘frontier’. So the edges are a mix of pioneering local institutions — from community groups to councils — and pockets of contemporary practice in central government, often under a rebellious leader.

A recent example of the opposite of moral agency. Last year I helped my 92 year-old grandad to apply for financial support for my Nan’s care, via Hertfordshire Council. It took a year for the support to arrive, and was a huge battle. The council eventually made the payment, along with a huge back-payment, and they immediately started sending aggressive and impersonal debt collection letters — apparently automated — demanding that my grandad pay back a share of the money. At no point did anyone in the chain seem to have the moral agency and discretion to say: ‘maybe sending this letter isn’t a good idea’.

If you want to go deeper into institutions and how they behave, I recommend Mary Douglas, How Institutions Think; Elinor Ostrom, Institutional Diversity; and Brigette Berger et al, The Homeless Mind. They help us see that the social bonds that tie us into institutional patterns of behaviour are much stronger than the electromagnetic bonds that bind a physical material, which is why it’s easier to reshape a block of iron than it is to reshape a government department. I extended this analogy in this post on the material properties of institutions.